one $25 Amazon Gift Card, and one (signed) Quintaglio Ascension Trilogy in trade paperback

Follow the tour HERE for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

![]()

Far-Seer

The Quintaglio Ascension Book 1

by Robert J. Sawyer

Genre: SciFi Fantasy

Sixty-five million years ago, aliens transplanted Earth’s dinosaurs to another world. Now, intelligent saurians — the Quintaglios — have emerged. Afsan, the Quintaglio counterpart of Galileo, must convince his people of the truth about their place in the universe before astronomical forces rip the dinosaurs’ new home apart.

The Face of God is what every young saurian learns to call the immense, glowing object which fills the night sky on the far side of the world. Young Afsan is privileged, called to the distant Capital City to apprentice with Saleed the court astrologer. But when the time comes for Afsan to make his coming-of-age pilgrimage, to gaze upon the Face of God, his world is changed forever- for what he sees will test his faith… and may save his world from disaster!

Fossil Hunter

The Quintaglio Ascension Book 2

Toroca, a Quintaglio geologist, is under attack for his controversial new theory of evolution. But the origins of his people turn out to be more complex than even he imagined, for he soon discovers the wreckage of an ancient starship — a relic of the aliens who transplanted Earth’s dinosaurs to this solar system. Now Toroca must convince Emperor Dybo that evolution is true; otherwise, the territorial violence the Quintaglios inherited from their tyrannosaur ancestors will destroy the last survivors of Earth’s prehistoric past.

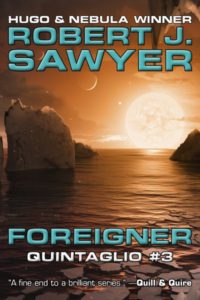

Foreigner

The Quintaglio Ascension Book 3

In Far-Seer and Fossil Hunter, we met the Quintaglios, a race of intelligent dinosaurs (evolved descendants of dinosaurs rescued in prehistory from Earth), and learned of the threat to their very existence. Now they must quickly advance from a culture equivalent to our Renaissance to the point where they can leave their planet.

While the Quintaglios rush to develop space travel, the discovery of a second species of intelligent dinosaurs rocks their most fundamental beliefs. Meanwhile, blind Afsan — the Quintaglio Galileo — undergoes the newfangled treatment of psychoanalysis, throwing everything he thought he knew about his violent people into a startling new light.

![]()

Robert J. Sawyer — called “the dean of Canadian science fiction” by The Ottawa Citizen and “just about the best science-fiction writer out there these days” by The Denver Rocky Mountain News — is one of only eight writers in history (and the only Canadian) to win all three of the science-fiction field’s top honors for best novel of the year:

- the World Science Fiction Society’s Hugo Award, which he won in 2003 for his novel Hominids;

- the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America’s Nebula Award, which he won in 1996 for his novel The Terminal Experiment;

- and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, which he won in 2006 for his novel Mindscan.

According to the US trade journal Locus, Rob is the #1 all-time worldwide leader in number of award wins as a science fiction or fantasy novelist. Recent honors include the first-ever Humanism in the Arts Award from Humanist Canada, the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal from the Governor General of Canada, the Hal Clement Award for Best Young Adult Novel of the Year (for Watch), and a Lifetime Achievement Aurora Award from the Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Association — the first such award given to an author in thirty years, and only the fourth such ever bestowed.

The 2009-2010 ABC TV series FlashForward was based on his novel of the same name, and Rob was a scriptwriter for that series.

Maclean’s: Canada’s Weekly Newsmagazine says, “By any reckoning, Sawyer is among the most successful Canadian authors ever,” and The New York Times calls him “a writer of boundless confidence and bold scientific extrapolation.” The Canadian publishing trade journal Quill & Quire named Rob one of “the thirty most influential, innovative, and just plain powerful people in Canadian publishing” (the only other authors making the list were Margaret Atwood and Douglas Coupland).

Rob’s novels are top-ten national mainstream bestsellers in Canada, appearing on the Globe and Mail and Maclean’sbestsellers’ lists, and they’ve hit #1 on the science-fiction bestsellers’ lists published by Locus, Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, Amazon.co.uk, and Audible.com. His twenty-three novels include Red Planet Blues, Triggers, Calculating God, and the “WWW” trilogy of Wake, Watch, and Wonder, each volume of which separately won the Aurora Award — Canada’s top honor in science fiction — for Best Novel of the Year.

Rob — who holds honorary doctorates from the University of Winnipeg and Laurentian University — has taught writing at the University of Toronto, Ryerson University, Humber College, and The Banff Centre. He has been Writer-in-Residence at the Richmond Hill (Ontario) Public Library, the Kitchener (Ontario) Public Library, the Toronto Public Library’s Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy, Berton House in Dawson City, the Canadian Light Sourcesynchrotron, and the Odyssey Workshop.

Rob has given talks at hundreds of venues including the Library of Congress and the National Library of Canada, and beenkeynote speaker at dozens of events in places as diverse as Los Angeles, Boston, Tokyo, Beijing, and Barcelona. He was born in Ottawa in 1960, and now lives just west of Toronto.

Website * Blog * Facebook * Twitter * Amazon * Goodreads

Most of your novels take place on Earth in the present or very near future. Why?

My books that are set off Earth – Far-Seer, Fossil Hunter, and Foreigner, plus Starplex –are my poorest-selling titles, even though I think they’re among the best books I’ve ever written.

Where did the names in The Quintaglio Trilogy come from?

Sometimes I name characters in honor of friends of mine. Afsan’s name is the acronym for my high-school science-fiction club (which I founded) backwards: NASFA, the Northview Association for Science Fiction Addicts. Det Yenalb is Ted Bleaney and Mar-Biltog is Richard Marshall Gotlib, both of whom were members of NASFA and are still my friends today.

Does the fact that you are a Canadian influence your work?

Yes, it does, and hugely. Canada is a nation of immigrants – we’re like the bridge of the Enterprise come to life. Canada is a vast social experiment in trying to craft a caring nation that values individual liberty; it’s the ideal test bed for science-fictional ideas.

I very much made a conscious effort to be conspicuously Canadian. When I was starting out, twenty-odd years ago, everyone was telling Canadian writers not to set their work in Canada if they wanted an international audience. I could understand that for mystery writers – the laws of the land are different on each side of the 49th parallel, and US readers might not understand Canadian jurisprudence. But for science fiction, the stricture seemed to make no sense: the laws of physics are the same on both sides of the border.

Of course, when I was starting out, there were no domestic Canadian publishers doing science fiction. Later on, a few small players emerged, and one or two actually survived. But it finally reached the point where Canadian publishers were vigorously courting me, and Penguin Canada went so far as to hire a new genre-fiction specialist to work with me and writers like me, and that’s terrific.

The knee-jerk desire to not set something in Canada is part of the Canadian national inferiority complex: we figure no one could possibly take any interest in us. But for a science-fiction writer, Canada is an amazing place. I’ve taken full advantage of such Canadian settings as the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (in Hominids and its sequels) and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (in Wake and its sequels).

Also, Canada at its best is a political and societal model for the twenty-first century – a compassionate, fiscally sound, high-tech, nonagressor, conservationist, liberal, semi-socialist democracy that celebrates multiculturalism and believes in gender equality and doesn’t discriminate on the basis of sexual preference – that the rest of the world needs to see, and I take pleasure in showing it to the readers of my books in 20 languages around the globe.

Overall, how do you portray the relationship between Canada and the States in your books?

I’m a dual citizen; I’m both an American and a Canadian. And I love both countries. But Canada is where I choose to live. That’s not lip service; many Canadians would love to go to the US and live if they had a choice, but they can’t get a green card or the immigration papers. Me, I can live and work freely in both countries, but I choose to stay in Canada. Still, I portray Canada and the US as fast friends, and we are. Despite our differences, some of which are profound, I always show us working together.

What are the major differences between Canadian science fiction and science fiction from other parts of the world?

I like to quip that American science fiction has happy endings, Canadian science fiction has sad endings, and British science fiction has no endings at all. Of course, there are exceptions, but I know of several Canadian SF writers who have been in conflict with our American editors over what we consider realistic and they consider depressing endings to our books.

What is your definition of science fiction?

My definition is this: “Science fiction is the mainstream literature of a plausible alternative reality.” That speaks to SF as a narrative mode: stories are written as though for an audience already familiar with the story’s milieu. An SF writer telling the story of a 22nd-century boomtown on Mars (Red Planet Blues) is writing as if the audience is familiar with that boomtown – or at least with its surrounding universe. It also stresses that the stories must be plausible – making an important distinction between SF and fantasy. SF stories plausibly could happen; fantasy stories never could happen – they’re actually antithetical genres.

Of course, some argue that time travel and faster-than-light travel are impossible, or at least highly improbable. I actually agree, and a lot of science fiction writers have come to agree as well in recent years; you see far, far less science fiction involving either of those things today than you did twenty-five years ago. Science fiction has a very special societal role: it explores the smorgasbord of possible futures, letting us choose which one we wish to live in. Fantasy, with its roots in the supernatural and its embracing of magic, may indeed have interesting psychological points to make, and it can certainly be valuable literature, but I find it interesting that fantasy fans constantly try to subsume science fiction into the fantasy genre. You never see the reverse – science fiction fans saying that fantasy, with its magic and archetypal characters, is a subset of science fiction. I think that’s because, down deep, that fantasy fans recognize the importance and value of ambitious science fiction, and want to be able to claim it for their own field.

I’ve always felt that science fiction has much more in common with mystery than with fantasy. Science fiction and mystery both prize rational thought, and both ask the reader to carefully pick up the clues the author has salted into the text – in mystery, of course, to solve the crime, and in science fiction to puzzle out the unfamiliar backdrop against which the story is being told.

Your own work tends to straddle the science fiction and mystery genres, but do you think we should even have labels? Do they help or hurt?

In the United States, they’re a necessary evil – so many books are published, they have to be organized somehow for browsing. But in general, they hurt. I’m proud to call myself a science-fiction writer – my website is sfwriter.com and my car’s license plate says SFWRITER – but in Canada, I’m mostly thought of as a writer, period, and my audience is much, much wider than it is in the States.

There are way, way, way more people who read Michael Crichton, Audrey Niffenegger, or J.D. Robb than there will ever be readers of any writer published as science fiction you care to name. A lucky few have left the category – William Gibson is no longer published as SF – but mostly if you start there, you’re stuck there. Oh, we may be able to see, and understand, the stars better than just about any other writers alive, but there’s a definite glass ceiling on our sales, imposed by the simple fact that 95% of book buyers never, ever go into the science fiction section, because they can’t imagine it holds anything of interest for them.